Branegan’s Wake

Discover Norfolk Magazine, July 2022

1783 was one of the hottest years on record in England, and one of the deadliest. All across Europe in fact, the mercury climbed to historic levels, harvests wilted and failed, waterways dwindled, and every man, woman and child suffered. By late summer, field hands and animals alike were dying on their feet, dropping where they stood in the searing heat. Conditions were not helped by the poor quality of the air, which for weeks had been stifled by a rank dry fog, stinking of sulphur, thickly blanketing the country (and much of the continent). Its affect was such that – on evenings when sunsets could actually be seen – the colours painting the sky seemed otherworldly, and come full-dark the moon seemed almost to be bleeding.

The fog was widely believed to originate in Oppido Mamertina, Calabria, a city clinging to the rough slopes of the Aspromonte range, on Italy’s southern tip, where since February a series of powerful earthquakes had devastated the region, killing some 35,000 and conjuring tsunamis that ravaged the coast for miles inland. The real culprit was actually to be found much further north though, in Iceland. Hidden deep in the open wound of the Laki fissure. Laki, a 15-mile rent in the earth’s crust, began spewing massive quantities of sulphur dioxide, chlorine, and fluorine (along with three cubic miles of lava) on June 8th, in an eruption that would eventually go on to release over 100-million tons of toxic gas into the atmosphere, claiming the lives of half the country’s population – and setting in motion an environmental catastrophe.

700-miles to the south, on Britain’s sunburnt shores – as beasts died in their thousands, the moon wept blood, and gasping children coughed their last – the true source of the poisonous cloud remained a mystery. Theories swirled, and many even came to believe this was the apocalypse: the beginning of the end of the world. For a 30-year-old brigand named James Branegan, sweating in the dock at Southampton Gaol, it might just as well have been.

Branegan was one of three men who, late one evening on the dust-blown road from Southampton to Winchester, had happened upon a lone traveller, John Cutler. Here, if the record is to be believed, the trio violently assaulted and robbed Cutler, falling on him from behind and relieving him of both his purse and his health. The pickings were slim (little more than a few meagre shillings), but in an age when the government’s so-called Bloody Code of justice meant simply stealing a handkerchief could see you dancing the Tyburn jig, highway robbery on the King’s Road carried the same penalty as murder. Soon apprehended, the three were tried, found guilty, and sentenced to hang.

Fortuitously for their necks, Britain’s practice had long been to send its convicted criminals as far away as possible. (Extreme rehabilitation if you like.) Ridding them of the temptations of their old haunts (and the nation of its “Offensive rubbish”) and providing an economical source of empire-expanding labour into the bargain. Their sentences were commuted to transportation, and the 50,000 indentured souls already shackled on American soil had six more working hands to look forward to.

Until passage on a suitable ship could be arranged, the men languished in Plymouth, residing for nearly a year in the dank bowels of the decommissioned warship Dunkirk. The hulk, as these derelict ships were known, just one of a clutch of such holding pens, pressed into temporary service as prisons on England’s coast: rotting, pestilent places, where disease and violence ran rife, and as many as a quarter of those packed in would die before release. But Branegan survived, and in March of 1784, such as was left of him joined 178 fellow convicts aboard the Mercury – a privateer bound for Virginia – and a new life in the New World. It was to be a voyage notable both for its brevity, and its mutiny.

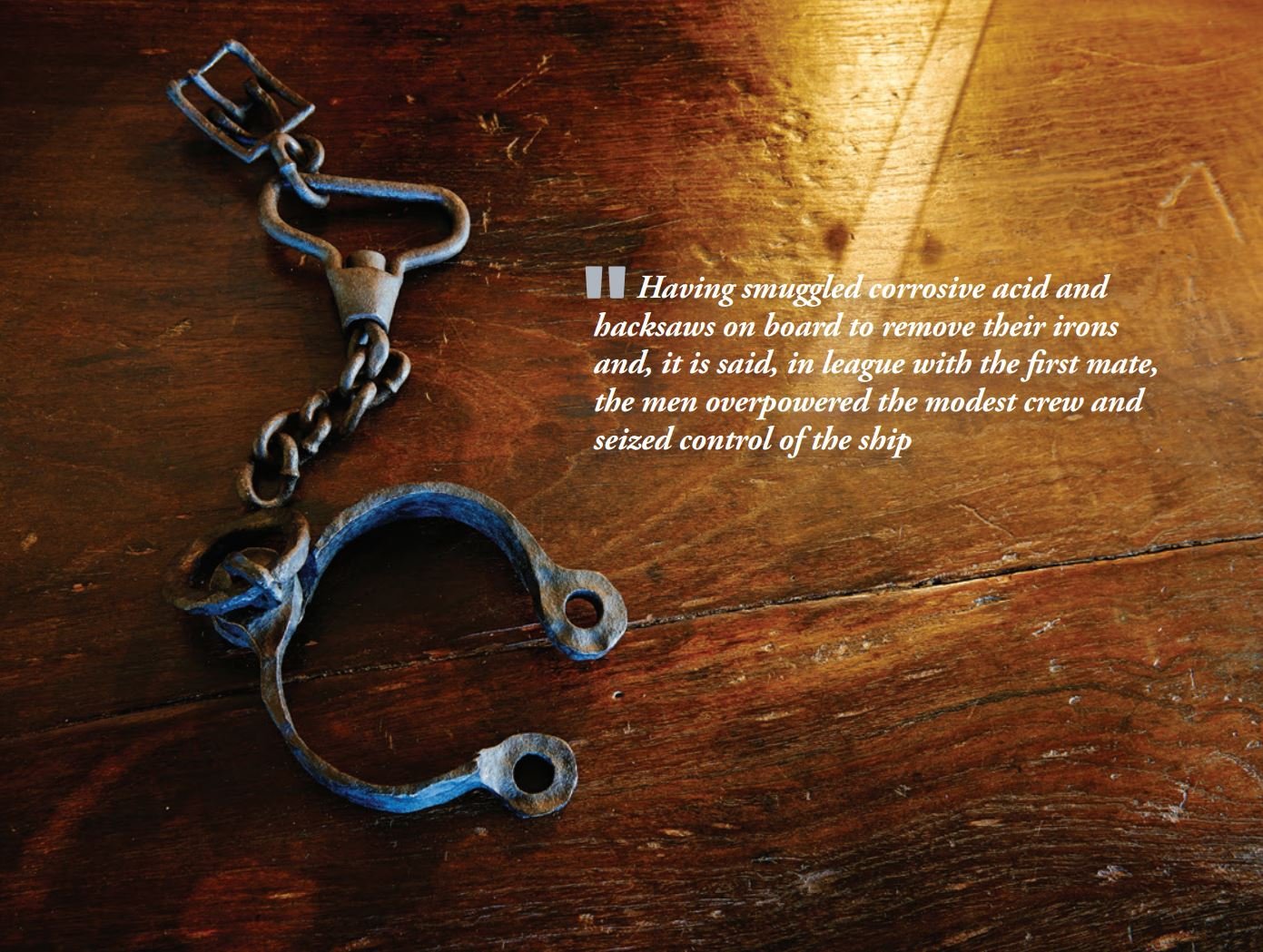

Barely six days from port, just off the Scilly Isles in the early hours of the morning, the prisoners revolted. Having smuggled corrosive acid and hacksaws on board to remove their irons and, it is said, in league with the first mate, the men overpowered the modest crew and seized control of the ship. There were able seamen aboard, certainly sufficient to make good an escape under sail, but most were desperate men – and such men are unpredictable. The mutineers quarrelled, foundered, and in less than a week abandoned ship: putting in off Torbay, on the southwestern tip of the English coast. Most were apprehended here, making for shore in small rowing boats, collared by the crew of HMS Helena (a 14-gun navy sloop). And whilst a few did get as far abroad as London, all were eventually recaptured. Branegan, for his part, was once again sentenced to hang. And that should probably have been the end of his story. But fate – and the prevailing political winds of the time – once again intervened. (Though if asked later, he may well have preferred the rope.)

For three more long years he rotted on the Dunkirk – mired on the muddy banks of the Hamoaze estuary, amongst the stench and decay. Britain’s loss in the American Revolutionary War dooming him, and many others, to simply wait until some new untamed corner of the empire could be found to send them to. Finally, in March of 1787, he stepped off the Dunkirk for what would be the last time. Exchanging one cramped berth for another and boarding the Charlotte: 105 feet of newly built three-masted barque. Part of a small flotilla of ships bound for Botany Bay, in what is now known collectively as the First Fleet.

The journey that followed is hard to imagine. With close to 200 souls on a ship little bigger than two family homes, each passenger would have had something approximating the size of a telephone box in which to subsist, for 10 months, over 15,000 miles of treacherous open ocean. How must he have felt as the Charlotte eventually made landfall in Port Jackson? (In what is now known as Sydney harbour.) A man whose feet had barely touched solid ground in five hard years.

Things got no easier on land. Life was unremittingly tough in the newly established colony. Indeed, a challenging climate, hostile locals, aggressive wildlife, and dwindling provisions quickly brought the settlement to the brink of starvation, and little more than two years after the First Fleet’s arrival, Port Jackson was on its knees. Governor Arthur Phillip had little choice to act. In desperation – and in part because of its growing reputation as a “breadbasket” he despatched the fleet’s flagship, the Sirius, under Captain John Hunter (a Scotsman who would go on to succeed Phillip as Governor) 1000 miles northeast, to the smallest British outpost in the Pacific, in the hope of taking on supplies, and easing the strain. Branegan – amongst Marines, convicts, and their children – once again took to the water, setting sail for Norfolk Island.

The Sirius, sailing in tandem with the First Fleet’s only other remaining capable naval ship, the Supply, made good time, approaching the island’s notoriously treacherous coast in the early hours of March 13th. “At two o’clock in the morning, we made Norfolk Island, which I did not expect we should have done quite so soon, but the easterly current, which is commonly found here, had been strong” wrote Hunter in his journal. It being full dark though, he waited until daylight to attempt landfall. But as the sun crept above the horizon, and with the wind freshening from the southwest whipping the surf into a frenzy of white-water, the Leith-born captain had little choice but to bear away from Sydney Bay, lest he be dashed off the rocks. Instead, he “Ran round to the north-east side of the island, to Cascade-bay, where, after a few days of moderate weather, and an off-shore wind, it was possible to land.”

With a break in the weather, Hunter somehow managed to disembark all hands, landing them directly onto an exposed and jagged promontory. But his luck was not to last. On the 19th of March, with the wind swinging cruelly into brutal on-shore gusts, the Sirius – with the majority of its precious remaining stores still on board – was dashed against the reef at Slaughter Bay, and there she foundered.

Captain, crew, and the islands’ settlers alike could only watch from the sand as the First Fleet’s flagship (and one of Norfolk’s only connections to the outside world) was pounded repeatedly against the reef, driven by heavy seas and high winds, until at last the wreck was stuck fast, in relatively shallow water. By now disconsolate, and doubtless pushed to breaking point by the stresses of the long and challenging approach, Hunter inexplicably agreed to allow two convict volunteers to swim out to the sinking vessel, that the livestock might be rescued. Amongst their number was a one-time brigand from Southampton, by now more at home on deck than on shore. James Branegan was once again shipbound.

Much is said about the effects of rum on men at sea – for good and ill. But few would argue they trended towards the negative when Branegan and his dripping accomplice, left to their own devices and, for perhaps the first time in seven years, unguarded, broke into the ship’s liquor stores and guzzled themselves daft on grog, failing to emancipate a single beast (and setting the ship ablaze for good measure). One can only imagine the freedom they finally felt: dancing on the deck, the raw liquor burning their throats, feeling the waves pound onto them as the lights of Sydney Bay twinkled – and the furious shouts blended with the splashing of Marines crashing towards them through the surf…