The Road to Restoration

Magical green enclaves lend the place an ancient, fairytale atmosphere. As if at any moment a malevolent kelpie might peer out from behind a moss-covered boulder.

The Scotsman, Aug 2022

To reach the shores of Wolf Island, off the western edge of the isle of Mull, one must first negotiate the Sound of Ulva: a narrow, rock-and-islet-strewn strait, linking the sea lochs of na Keal and Tuath. To do this, would-be passengers summon the ferry by turning a hand-painted red wooden sign, located high on the pier – and waiting. The craft, when it arrives, is perhaps the smallest ferry, making the briefest Atlantic crossing in all of Scotland. And if there’s a better way to spend six pounds, I’ve yet to find it.

Of course, despite the fact that Wolf Island is incalculably cooler, few have called the place by its Viking name for a thousand years. Today it’s known as Ulva, a corruption of the Norse. A remote, compact, and heartstoppingly beautiful island, 20 winding miles and 40 waterborne seconds from Tobermory.

From the head of the slipway, the Boathouse restaurant commands spectacular views of the water. Promising fine local seafood, home baking, and, as my travel companion is excited to point out, the tantalising prospect of ‘A wee coffee’, it alone looks worth the trip. But we’ll be back to sample their fare in a few hours. First, with the sun glittering off the loch, and the breeze, with luck, whipping away the midges, we’ve an island to explore.

Of the several well marked routes, we choose the Ormaig and Kilvekewen walk. Eight miles, all told, or about a four-hour round trip. Making for the southern coast, the path first coils past the old boathouse, then Sheila’s cottage, a restored thatch and stone croft house. We pass a little industry just back from the water’s edge. Amphibious all-terrain vehicles and site huts, evidence of the housing renovation programme. Just one of the ways the community – which bought the island in 2018 – is trying to bring people, and with them social and economic security, back to the island. As we head deeper inland from the coast, a hush descends. A heavy silence broken only by the trickling of the burn, and the sibilant whisper of a waterfall.

It still strikes me as strange, and rather wonderful, stumbling upon these pockets of mature native woodland in the Hebrides, particularly broadleaf trees. The low, exposed islands of nearby Coll, Tiree, Rùm, and Eigg – places I love dearly – have spectacular beaches, but next to no trees. Here there are venerable old oaks, laburnum, cherry, sycamore and walnut. Even the occasional elm defying the odds. Though much of the island is exposed moorland, bracken and machair, these magical green enclaves lend the place an ancient, fairytale atmosphere. As if at any moment a malevolent kelpie might peer out from behind a moss-covered boulder.

Out in the open it’s warm, thirsty work. The track continues to climb as the trees fall away. In places it’s boggy and treacherous. Once, 600 people made their homes here. 16 villages spread out over 12 rocky kilometres, mostly kelp farmers. Decimated by famine, and the ravages of the clearances, by the beginning of the twentieth century their numbers had dwindled drastically. Today the population stands at just 11. After an hour or so of rough going, during which we are entirely alone, the coast appears below us. The small isles of Little Colonsay, Staffa, and Inch Kenneth rising like the backs of great emerald monsters. In the distance, the outstretched arm of southern Mull, Iona, and beyond that – if one could see so far – clear water to Malin Head: the uppermost tip of Ireland.

Three hours later, footsore and famished, back at the Boathouse, it’s time for lunch. We find a wooden table perched on its own, on a little grassy rise. With the island to our backs, it looks out over Loch na Keal and the mountains beyond. Two yachts ease their way up the channel. It’s too hot for coffee, so instead we (by which I mean I) partake of two ice cold beers, in quick, glorious succession.

Mark Elliot and Brendan Tyreman took over the restaurant’s lease a little over a year ago, relocating to the island from Edinburgh and fulfilling a rural dream that many might envy, but few would so impressively embrace. Their menu is short and flexible, responsive to the availability of the freshest produce, and all the better for it. Locally sourced seafood, Mull cheeses, homemade seaweed chutney and slowly fermented home baked bread. Seasonal ingredients, imaginatively prepared. It’s refreshing, frankly, with views like these – and a literally captive audience – to find such obvious care on the plate. We opted for the Tobermory smoked trout, with capers, red onion and mayonnaise, and creel caught Ulva crab, served with salad and homemade pickles. The trout is subtle, smoky, luxuriant (and plentiful), pairing well with the punchy citrus tang of the capers, and the crisp sweet onions; the potted crab, smothered onto thick, soft bread, is rich and mouthwateringly buttery. In fact, I’d say the food, like the view, is restorative.

Ferries to Ulva run Mon-Fri, 9-5:30 + Sundays in June, July, Aug. No ferries on Saturdays. The Boathouse is open 9-5 Mon-Fri + 11-5 on Sundays. Closed Saturdays.

Branegan’s Wake

Discover Norfolk Magazine, July 2022

1783 was one of the hottest years on record in England, and one of the deadliest. All across Europe in fact, the mercury climbed to historic levels, harvests wilted and failed, waterways dwindled, and every man, woman and child suffered. By late summer, field hands and animals alike were dying on their feet, dropping where they stood in the searing heat. Conditions were not helped by the poor quality of the air, which for weeks had been stifled by a rank dry fog, stinking of sulphur, thickly blanketing the country (and much of the continent). Its affect was such that – on evenings when sunsets could actually be seen – the colours painting the sky seemed otherworldly, and come full-dark the moon seemed almost to be bleeding.

The fog was widely believed to originate in Oppido Mamertina, Calabria, a city clinging to the rough slopes of the Aspromonte range, on Italy’s southern tip, where since February a series of powerful earthquakes had devastated the region, killing some 35,000 and conjuring tsunamis that ravaged the coast for miles inland. The real culprit was actually to be found much further north though, in Iceland. Hidden deep in the open wound of the Laki fissure. Laki, a 15-mile rent in the earth’s crust, began spewing massive quantities of sulphur dioxide, chlorine, and fluorine (along with three cubic miles of lava) on June 8th, in an eruption that would eventually go on to release over 100-million tons of toxic gas into the atmosphere, claiming the lives of half the country’s population – and setting in motion an environmental catastrophe.

700-miles to the south, on Britain’s sunburnt shores – as beasts died in their thousands, the moon wept blood, and gasping children coughed their last – the true source of the poisonous cloud remained a mystery. Theories swirled, and many even came to believe this was the apocalypse: the beginning of the end of the world. For a 30-year-old brigand named James Branegan, sweating in the dock at Southampton Gaol, it might just as well have been.

Branegan was one of three men who, late one evening on the dust-blown road from Southampton to Winchester, had happened upon a lone traveller, John Cutler. Here, if the record is to be believed, the trio violently assaulted and robbed Cutler, falling on him from behind and relieving him of both his purse and his health. The pickings were slim (little more than a few meagre shillings), but in an age when the government’s so-called Bloody Code of justice meant simply stealing a handkerchief could see you dancing the Tyburn jig, highway robbery on the King’s Road carried the same penalty as murder. Soon apprehended, the three were tried, found guilty, and sentenced to hang.

Fortuitously for their necks, Britain’s practice had long been to send its convicted criminals as far away as possible. (Extreme rehabilitation if you like.) Ridding them of the temptations of their old haunts (and the nation of its “Offensive rubbish”) and providing an economical source of empire-expanding labour into the bargain. Their sentences were commuted to transportation, and the 50,000 indentured souls already shackled on American soil had six more working hands to look forward to.

Until passage on a suitable ship could be arranged, the men languished in Plymouth, residing for nearly a year in the dank bowels of the decommissioned warship Dunkirk. The hulk, as these derelict ships were known, just one of a clutch of such holding pens, pressed into temporary service as prisons on England’s coast: rotting, pestilent places, where disease and violence ran rife, and as many as a quarter of those packed in would die before release. But Branegan survived, and in March of 1784, such as was left of him joined 178 fellow convicts aboard the Mercury – a privateer bound for Virginia – and a new life in the New World. It was to be a voyage notable both for its brevity, and its mutiny.

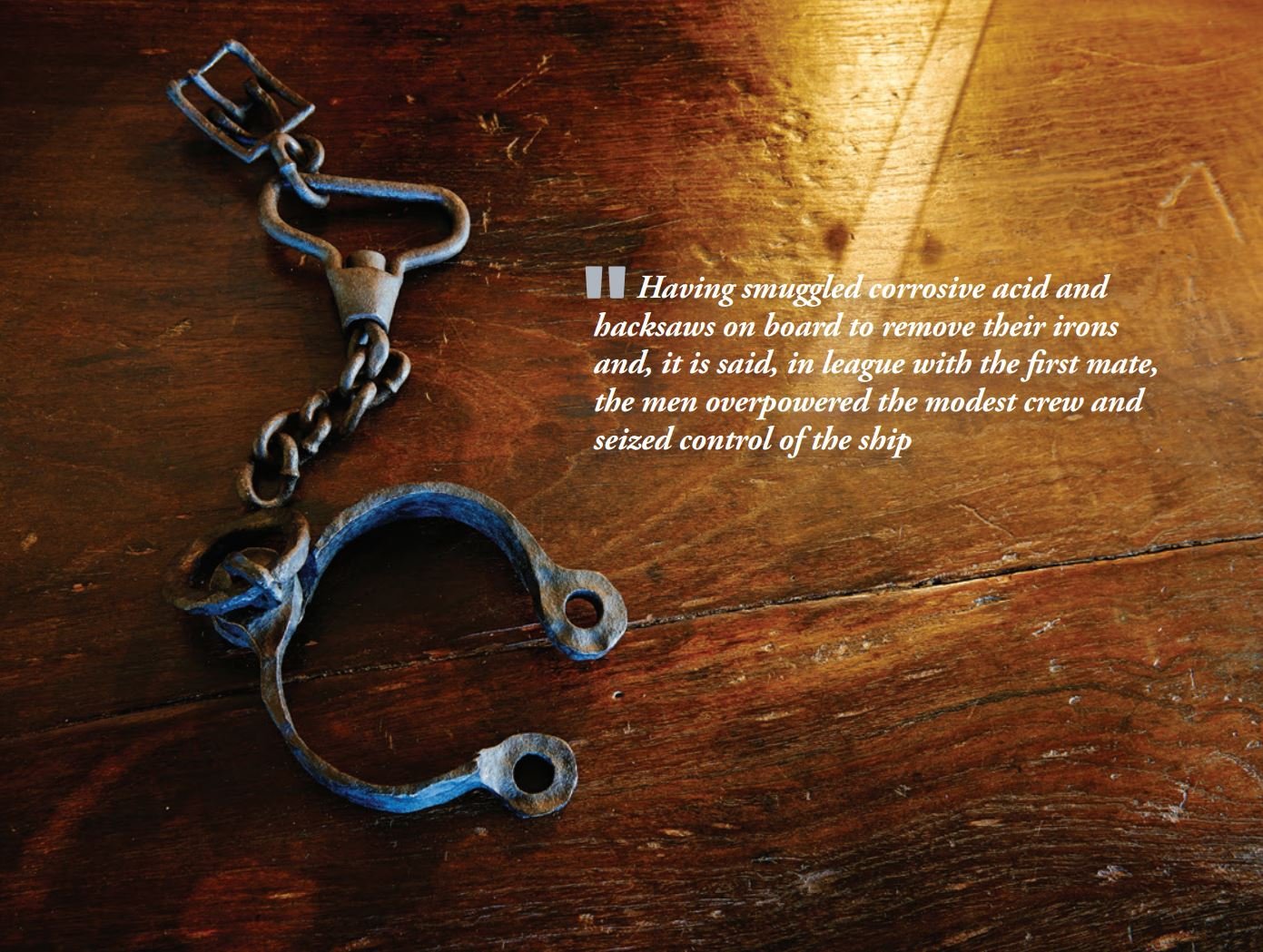

Barely six days from port, just off the Scilly Isles in the early hours of the morning, the prisoners revolted. Having smuggled corrosive acid and hacksaws on board to remove their irons and, it is said, in league with the first mate, the men overpowered the modest crew and seized control of the ship. There were able seamen aboard, certainly sufficient to make good an escape under sail, but most were desperate men – and such men are unpredictable. The mutineers quarrelled, foundered, and in less than a week abandoned ship: putting in off Torbay, on the southwestern tip of the English coast. Most were apprehended here, making for shore in small rowing boats, collared by the crew of HMS Helena (a 14-gun navy sloop). And whilst a few did get as far abroad as London, all were eventually recaptured. Branegan, for his part, was once again sentenced to hang. And that should probably have been the end of his story. But fate – and the prevailing political winds of the time – once again intervened. (Though if asked later, he may well have preferred the rope.)

For three more long years he rotted on the Dunkirk – mired on the muddy banks of the Hamoaze estuary, amongst the stench and decay. Britain’s loss in the American Revolutionary War dooming him, and many others, to simply wait until some new untamed corner of the empire could be found to send them to. Finally, in March of 1787, he stepped off the Dunkirk for what would be the last time. Exchanging one cramped berth for another and boarding the Charlotte: 105 feet of newly built three-masted barque. Part of a small flotilla of ships bound for Botany Bay, in what is now known collectively as the First Fleet.

The journey that followed is hard to imagine. With close to 200 souls on a ship little bigger than two family homes, each passenger would have had something approximating the size of a telephone box in which to subsist, for 10 months, over 15,000 miles of treacherous open ocean. How must he have felt as the Charlotte eventually made landfall in Port Jackson? (In what is now known as Sydney harbour.) A man whose feet had barely touched solid ground in five hard years.

Things got no easier on land. Life was unremittingly tough in the newly established colony. Indeed, a challenging climate, hostile locals, aggressive wildlife, and dwindling provisions quickly brought the settlement to the brink of starvation, and little more than two years after the First Fleet’s arrival, Port Jackson was on its knees. Governor Arthur Phillip had little choice to act. In desperation – and in part because of its growing reputation as a “breadbasket” he despatched the fleet’s flagship, the Sirius, under Captain John Hunter (a Scotsman who would go on to succeed Phillip as Governor) 1000 miles northeast, to the smallest British outpost in the Pacific, in the hope of taking on supplies, and easing the strain. Branegan – amongst Marines, convicts, and their children – once again took to the water, setting sail for Norfolk Island.

The Sirius, sailing in tandem with the First Fleet’s only other remaining capable naval ship, the Supply, made good time, approaching the island’s notoriously treacherous coast in the early hours of March 13th. “At two o’clock in the morning, we made Norfolk Island, which I did not expect we should have done quite so soon, but the easterly current, which is commonly found here, had been strong” wrote Hunter in his journal. It being full dark though, he waited until daylight to attempt landfall. But as the sun crept above the horizon, and with the wind freshening from the southwest whipping the surf into a frenzy of white-water, the Leith-born captain had little choice but to bear away from Sydney Bay, lest he be dashed off the rocks. Instead, he “Ran round to the north-east side of the island, to Cascade-bay, where, after a few days of moderate weather, and an off-shore wind, it was possible to land.”

With a break in the weather, Hunter somehow managed to disembark all hands, landing them directly onto an exposed and jagged promontory. But his luck was not to last. On the 19th of March, with the wind swinging cruelly into brutal on-shore gusts, the Sirius – with the majority of its precious remaining stores still on board – was dashed against the reef at Slaughter Bay, and there she foundered.

Captain, crew, and the islands’ settlers alike could only watch from the sand as the First Fleet’s flagship (and one of Norfolk’s only connections to the outside world) was pounded repeatedly against the reef, driven by heavy seas and high winds, until at last the wreck was stuck fast, in relatively shallow water. By now disconsolate, and doubtless pushed to breaking point by the stresses of the long and challenging approach, Hunter inexplicably agreed to allow two convict volunteers to swim out to the sinking vessel, that the livestock might be rescued. Amongst their number was a one-time brigand from Southampton, by now more at home on deck than on shore. James Branegan was once again shipbound.

Much is said about the effects of rum on men at sea – for good and ill. But few would argue they trended towards the negative when Branegan and his dripping accomplice, left to their own devices and, for perhaps the first time in seven years, unguarded, broke into the ship’s liquor stores and guzzled themselves daft on grog, failing to emancipate a single beast (and setting the ship ablaze for good measure). One can only imagine the freedom they finally felt: dancing on the deck, the raw liquor burning their throats, feeling the waves pound onto them as the lights of Sydney Bay twinkled – and the furious shouts blended with the splashing of Marines crashing towards them through the surf…

Eat, Sleep, Row…Repeat

The Scotsman, Feb 2022

Night shift is a demanding time in the Talisker Atlantic rowing challenge. Thousands of miles from home on an open boat. Almost impossibly far from family and friends in a sea so black it merges with the sky, robbing you of balance and bearings. Rarely more so for the crew of Scotland’s Five in a Row than an evening roughly two-thirds of the way through the event. January 7th. The night of the daggerboard.

SS2, the 28 feet of fiberglass that had become their home, was then approximately 800 nautical miles from landfall in the West Indies. They had not seen another vessel for three weeks. Clive, Duncan, Ross, Ian, and Fraser were physically and mentally exhausted, struggling to make clear decisions. Smoked almost to the filter by sleep-deprivation, physical and emotional effort, and they are willing to admit, fear.

“The seas were huge; I don’t know how big. It was pitch dark, and you couldn’t see what was coming. It was…I mean it was absolutely terrifying.” says Duncan, back there for a moment, isolated on the churning obsidian swell. What he doesn’t say, but what the GPS records show, is that the boat was also moving horribly fast. Surfing at times. Strong tailwinds pushing the speedometer to max out at nearly13 knots over a 48-hour period. Close to 14mph, and more than triple their normal rate of progress.

“So we’d been drifting badly south for some time, and late that night, Clive and I were on shift, just about done in from lack of sleep and frankly scared. The decision was made to put in the daggerboard (a slim slot-in keel), just to try and hold our position.”

“The seas had been big for days, crashing in from all sides and making it difficult to even get the oars into the water.” adds Clive. “But after that something else was different. We seemed to have to wrestle and fight, just to keep the boat from trying to corkscrew around.”

Four shifts and eight challenging hours later, Ian and Fraser found themselves alone on deck, battling to keep the boat steady in the wrenching seas. The daggerboard was still down.

“You’d find yourself at the top of a vertical wall of water, looking down at 30 ft of nothing and thinking: if this was a cliff...” recalls Ian, with a shake of the head, his mind’s eye still seeing it clearly less than two weeks later. “I’d already been unseated three times by waves at that point and had moved to the bow (front) seat. Then of course a rogue came in on the bow side and knocked me over!”

“I remember I pulled Bairdy back into the boat” continues Fraser, “I was at stroke (rear) and ended up right up in the bow! My shoes were still clamped in the stern rowing position.”

“It was a hellish night” mutters Ian, “and by that stage we were getting so hammered, and so turned around that the auto-helm couldn’t correct, so the alarm was sounding. Then the navigation screens went blank, and we had absolutely no idea where we were, or which direction we were facing. And Fraser just kept shouting: We’re sitting ducks! We’re sitting ducks!”

“It was really reassuring from inside the cabin.” chimes in Duncan. And the five weather-beaten, wild-haired men sitting around the table grimace, sharing a wry smile that few others will ever really understand.

I first met Scotland’s only entrants in this year’s transatlantic race in the summer of 2021, at North Berwick harbour, where four out of the five men compete together as a successful skiff rowing crew. At the time they were well into their training for the event, but because of the pandemic still unable to even sit in the boat together as a team. They seemed fit and enthusiastic though, comfortable in each other’s company, which boded well for the long adventure to come. Even more so some five months later, when I ventured out on the Forth with Fraser, Duncan, and Ross for a final open water session before the boat was packed and shipped to Tenerife. But even the most optimistic probably wouldn’t have guessed that a podium position awaited them in Antigua, 3000 miles and 36 days from an emotionally charged start line, and half a world away from the grey North Sea.

In the end they placed third, by a hair, following a tense six-day battle for second. A gruelling effort that saw them arrive in Nelson’s Dockyard just hours after the Atlantic Flyers, and little more than a day off the winning pace. Posting the second fastest time for a five-man crew in the race’s history. But scarcely able to speak.

Today the spirit of the group still feels warm and clannish. If a little thinner round the middle, hands and bums a good deal more worn. And first I simply have to ask: was it what you expected?

“I mean…yes, in a way” says Clive, shifting a little uneasily in his seat. “Just…a lot more brutal!”

Brutal is an understatement. Rowing two hours on, two off, for close to a thousand hours in the sizzling summer temperatures and deep treacherous waters of the Atlantic. And as the only crew carrying the weight, supplies and bulk of five bodies, doing so on a heavier and significantly more cramped vessel than any other in the fleet.

That they finished well then, is beyond question, but things didn’t start out quite so smoothly. It was, they tell me, a race of two halves.

After days of official meetings, safety checks and briefings on the quay, their journey began as fourth out of a fleet of 36, surrounded by film crews and well-wishers gathered on San Sebastian’s sunny harbour wall on the morning of December 12th. “It was incredible. I had tears in my eyes,” admits Clive, “I think we all did.”

“Not long out of the harbour there was a pod of pilot whales following us” says Ross, “and I thought…so this is how it’s going to be. But pretty soon you realise it’s a very big ocean out there, and there’s a lot of space between things.”

Whales, land, and the fleet’s other boats soon drifted away, and the crew’s days adopted a standard rhythm. “Eat, sleep, row, repeat.” says Fraser, laughing at the memory, before expanding. “Two hours on - as hard as you can - and by the time you finish I mean you couldn’t do another two minutes. You crawl into your roasting cabin, cram in as many calories as you possible, wash as best you can, get as naked as you can, and sleep until about eight minutes before your next shift begins.”

Thanks to some initial teething problems though, wind shadows along the coast and ongoing niggles with the auto-helm, even following this punishing regimen Five in a Row had slipped back to eighth position after two weeks on the water. Mentally, as well as competitively, they were at their lowest ebb. So what changed?

“The GPS speedometer isn’t very accurate,” explains Ian, “but around Christmas time we started setting distance goals for the day, rather than concentrating on speed. We had tangible targets. The clock started at 8am. By 8pm you’d be trying to cover 40 miles or more, and so by 8am the following morning you’d be up over 80 miles. It became more methodical, strategic. We clocked in a few 90-mile days, and for a while we were the highest performing crew out there. Who knows, maybe if we’d figured that out earlier, we’d have done better…or more likely burned out sooner.”

“We were well back at that point” Ross recalls, “with a big, bunched pack catching up on us. But as soon as we started monitoring our progress closely, making incremental improvements, we began to pull away. And day-by-day we moved up steadily from the back.”

The change in tactics then, perhaps finding their groove, and the boat’s heading - working with Skip, their land-based weatherman, in an effort to benefit from tailwinds out of the south - clearly had a major impact on their climbing positions. But Clive has another theory as to the change in their fortunes.

“I’ll not deny setting distances made a difference,” he says, “but I think there’s more to it than that. Christmas, for me, was the lowest point by far. Look it was all tough, relentless, but Christmas eve, that night…I’d never felt so far away from home and the kids, my family. I don’t think any of us had. Because you knew the traditions. You knew exactly what would be going on at home. It was hard. I was very, very homesick.” At this the mood in the room sobers.

“So then…the next day” he says with purpose “Christmas is out of the way. We need to get home to our families. And the only way to do that is to row…quick. That realisation, I think, kicked in the more competitive side of things, for all of us. We stopped trying to just complete the race…and started competing in it.”

On December 26th the team began to receive daily status reports from Clive’s wife, and more detailed weather information from Skip, pinging in every morning at 8am. Days were broken down and broken down again into 15 minute increments, the whole crew obsessively monitoring progress. It worked. Little by little they reeled in the leaders, until they’d pulled their way to second place.

Inevitably, the sustained effort, saltwater and sweat took a toll on their bodies. Hands and muscles became brutalised by the work. Caribbean sun blistered fair Celtic skin. But by far the most problematic issues resulted from the endless hours of sitting. “A week from the finish, for all of us to one degree or another, our backsides were really suffering. I couldn’t even go in the water at that stage,” admits Clive. “I’m not just talking about scabby; your sit bones actually wear through your muscles. There’s literally nothing left. After forty minutes in the seat, if you’re lucky you go completely numb. It’s that…or screaming pain.”

Though they did have some painkillers on board, critically to alleviate this problem they also packed a wide variety of seat pads. “So the other thing you needed to consider when you staggered from your cabin,” says Ian with a grim smile, “was which combination of positions and pad types am I going to try today that’s different from yesterday!”

After five tough weeks at sea, the crew knew they were getting close to the finish. But it’s worth remembering that when you row in an event like this, you’re not just sitting in one place for weeks, you’re also travelling backwards for weeks. To the point where, especially if you’re overtired, you might even miss a few things.

“Ten in the morning on the final day. 6am local time,” recalls Duncan, “Clive and I had just finished a shift. I went to bed, but woke up half an hour into my sleep, which wasn’t like me at all. It was the silence. I just remember thinking; we must be close. But there was no craic on deck. No music, no banter, just total silence. I poked my head out of the door, and behind them there’s all this…land. My throat was hoarse for a week. Standing and shouting like a madman. I tell you it was worth it all, just for that moment.”

Five in a Row’s efforts though, were never just about adventure; pushing themselves to see how far they could go. The wider aim, and indeed the heart of the challenge, was always to raise awareness and funds for Reverse Rett, a medical research charity important to all of them. And in doing so incredibly well - finding their way onto so many radars - they also exceeded expectations in fundraising. “People have dug deep, and they are still digging deeper!” enthuses Fraser. He’s not wrong. To date they have raised close to £50,000 for the charity, not to mention inspiring a great many people to step out of their comfort zones. And at a time when most of us have never felt more trapped inside them, they perhaps deserve our thanks for that, almost as much as our respect for doing so well.

Time and Tide

The Scotsman, Nov 2021

Time and tide wait for no man. Chaucer said that, more than half a millennium ago, and it’s still true today. Particularly if you’re the one towing the boat, and you get a flat tyre on the way to the harbour. It’s eleven AM now. Had all gone to plan, Five in a Row would be skimming east across the Forth, gathering up some final training hours on a last cold-water run before being carefully packed and shipped to La Gomera, and the start line of the 2021 Talisker Atlantic Challenge. But it didn’t, and she’s not. Instead, boat and crew are poised on Port Edgar’s weedy slipway, where they have been waiting, for four hours.

Perennially cheerful skipper Duncan Hughes pokes his head out of the cabin, where he and Fraser Potter are making some last-minute adjustments, explaining away the delay with characteristic humour. From inside, there’s a loud banging and a piece of something crucial looking is tossed out onto the deck. “Weight-saving,” says Fraser, as he ducks back inside. Ross grins, Duncan giggles, and I am struck once again by the warm spirit of camaraderie that fortifies this close-knit team.

It’s been nearly four months since I last visited Ross McKinny, Fraser Potter, Clive Rooney, Ian Baird, and Duncan Hughes: Scotland’s only crew in this year’s trans-Atlantic race. Back in June, thanks to social distancing, they had yet even to sit in the boat together, let alone to scull her out on the water. But thankfully things have changed, and from the looks of their shoulders they’ve been taking the training seriously. All look formidably sturdy–and they’ll need to be. In December, they’ll be joining teams ranging from soloists to quintets, competing to pull themselves, unsupported, through three-thousand treacherous miles of open ocean, from the Canaries to the West Indies, against the clock and the forces of nature, for charity, pride, and the sheer bloody love of adventure–in what is dubbed by the organisers, the world’s toughest row.

By noon, the water’s high enough to launch safely. A fat 4x4 reverses into the murky flood tide, straps are released, and the craft shimmies free of her cradling trailer, floating gracefully out into the harbour. Fraser and Ross are already aboard, but with Clive and Ian unavailable today, I’m making up the numbers with another Cal; a svelte and steely-eyed rower whose crew have designs on buying the boat for the 2022 event. He looks powerfully familiar (later we’ll discover he is renowned actor Cal MacAninch) and as we walk together down the pontoon, I simply have to ask him why. Why would you want to put yourself through this? For the adventure, the challenge?

“The challenge, yes, and the charity” he says, in a precise Glaswegian burr. “And for my kids…to show them that anything is possible if you put your mind to it.”

With the boat alongside we leap on deck, rocking and lurching as everyone finds their positions, clipping into safety harnesses and perching as best we can as gear is stowed and oars are thrust out. What little space not given over to sliding rowers’ seats is awkward and utilitarian. Scant comfort can be found by leaning against the cabins. The sort of comfort generally associated with snuggling up to the luggage racks on cramped commuter trains. It’s rather like crouching in a very compact, very narrow minibus, with the wheels and seats removed and the bodywork cut away entirely a foot above floor level, bobbing around in the sea. (And if you’re trying to imagine it, can I suggest you don’t let your mind run to the five pitiless miles of ocean beneath you, or the thousand miles of it in front of you, or that you’ll be here for another month without a wash.)

“Backing, to starboard” shouts Ross, pushing away from the pontoon. And as we’re leaving the shelter of the harbour, it seems an opportune moment to enquire about navigation. “So is the plan just to row in as direct a line as possible, or do you all take different routes?” Ross, who is propped next to me, working the rudder with two long strings, answers in a gentle voice, “Pretty much. But it’s very weather dependent. We’ve an experienced weather-router on land, Stewart Robertson, who’ll be keeping track of us and helping to plot our course as we go, so it’s hard to predict accurately ahead of time. Some crews may head further out, to avoid bad weather, or find favourable winds. Wind can be a big help, but it can also be the enemy–the difference between a fast year and a slow, for everyone. We’ve a parachute anchor on board in case it gets really bad. Throw it out, should slow our backward drift a bit. At least that’s the theory.” As Fraser and Cal haul us bodily eastwards towards the sprawling red arcs of the Forth Bridge, I dwell for a moment on the heartbreak of watching your progress slip away, and shiver.

Just off Inverkeithing there is a change of personnel. Cal switches out with Duncan and hops up onto the cabin roof. The boat rolls heavily as they shift, and though it’s calm and we’ve no daggerboard out, it strikes me again just how keenly every movement will be felt out there by the whole crew. And that as tiredness creeps in and patience inevitably frays, the emotional, social demands of the race may become every bit as challenging as the physical.

“We’ve been lucky to work with an amazing performance psychologist” Duncan shouts across, to allay my concerns. “Katie Warriner. She works with Olympians, world champions,” he shakes his head, “different level. She’s built personal plans for us. Resilience, focus, communication. It’s really helped.”

I hope so.

We’ve been going a while, at what feels a decent clip, so I ask the obvious question: how long? “Well, the record is thirty-five days” says Duncan, sliding and pulling, sliding and pulling, “and if you’d asked me back in June, I’d have said thirty-five days. But now…look, I’ll be happy if I feel we’ve all pulled our hardest, done our best, even if it’s forty.”

“And Clive?” I ask, remembering that of all the crew, he is famously the most competitive.

“Thirty-four” the three of them reply in unison. And as if to punctuate their thought, Ross’s phone pings. It’s Clive, having somehow remotely tapped into the GPS and availed himself of our speed. Message reads: “Only three knots?! Dig in boys, come on!”

After lunch–fruit tea and a surprisingly tasty sachet of freeze-dried reindeer stew–it is, at last, my turn. “Follow the man in front” they tell me. “Just ignore all this water and keep your eyes on Ross’s back.” So I pull and slide, pull and slide, feeling the propulsion, but quickly feeling the effect in my lower back, too. A thousand hours of this? “Heels down, nipples up!” comes a shout from the boys. “Watch that form!”

I want to ask more about expectations, hopes. To dig further into their feelings as the starting line looms after so long in preparation. How they think they will react, what they may learn about themselves, and what fate might have in store. “So…” I begin, losing my rhythm, and clattering my oars into Ross’s. This time there is a different cry: “High Five!”

And perhaps they are better left unasked. After all, finding the answers to those questions is precisely what make this adventure so enticing to these brave men. That, and the promise of showing their children–and themselves–what’s possible if you really put your mind to it.

Charging: E-Biking the Isle of Mull

The Scotsman, Aug 2021

The road from Calgary - a hamlet so comely it inspired Colonel James Macleod to name Canada’s fourth biggest city after it - to the village of Salen, on the north-western edge of the isle of Mull, encompasses perhaps the most improbably rich slice of scenery in the Hebrides. Towering basalt cliffs, glittering aquamarine waters and bone white sands; vertiginous drops, priapic baronial piles and luxuriant, almost wanton jungle greenery. And that’s not even to mention the locals. Stags, seals, sea otters, soaring eagles, suicidal sheep, shaggy horny ginger cows big as barn doors and hurtling battered builders’ vans risking it all on the turn of a blind corner. But from where I’m standing now, things are rather less colourful.

Topping out a shade under two hundred metres, this lonely gravel turnout is a passing and a viewing place, four snaking uphill miles along the B8073 from the wide sweep of Calgary Bay. The air up here is noticeably chillier and the wind snaps and worries at my jacket. Rubble litters the close-cropped scrub and heather. No trees grow. Behind me, hunkered down and near invisible through the haze, the isles of Coll and Tiree lurk on the horizon. To my right, a clouds’ great shadow slithers over the Treshnish archipelago, its scattered skerries like so many uncut emeralds on a silken bedspread. Dead ahead, below and to the south, the olive mounds of Ulva and Gometra are skeined about the temples with a thin white mist, like smoke trickling from the corner of Clint Eastwood’s mouth.

Hunkering into my collar I peer down, ensuring there are no other vehicles labouring up the undulating singletrack. Satisfied I won’t be interrupted, I swing back into the saddle. Pedal once, twice, feeling first the surging push of the motor and then, with exhilarating urgency, the tingling rush of acceleration.

Forget what you think you know about electric bikes. Ignore those Italian waiter you’ve just asked for ketchup reactions from seasoned cyclists and stow your notions of sit up and beg commuting or, heaven forfend, cheating. In seriously hilly country, and few places do serious or hilly with more panache than the isle of Mull, what these machines really represent is freedom and wondrous accessibility. Ideal vehicles for the ninety nine percent of us not blessed with Chris Hoy thighs and a penchant for the gruelling, but who’d as soon not drag two tons of belching metal and engine along for the ride. To e-bike (I’m determined to coin a better name for it) is, from the very first turn of the pedals, to recapture those giggling childhood hours spent rocketing along on two wheels, at liberty to go wherever your fancy (rather than your fitness) may take you.

A sweeping S-bend with good visibility of oncoming traffic approaches. I’ve discovered I can hit even the steepest of these at full tilt which for me, given the collective weight of bulk and bike, is as close to forty miles per hour as makes no difference. Forefingers coiled around the brakes, I stand out of the saddle, start out wide and lean rather than steer. Wind roars in my ears, close and thrilling. Oiled bearings sing with the soft machine gun staccato of a fishing reel unspooling, gravel crunches under the tyres. And I am flying.

From somewhere deep inside, a whoop of joy involuntarily breaks for freedom through the massive grin I am wearing. It may be the first time I have ever done something so indecorous, so…American. The sheep in the verge seem to know it, shaking their heads and glaring, unimpressed, down long black noses.

Approaching Tostarie, the road rises and the motor hums gently with the turning cranks. I can feel my legs working, but it’s more bracing stroll than uphill grind, and at a stately fifteen miles an hour I have time to look about me at last. Jutting cliffs lend scale to the crumbling inlets fringing the headland. Cobalt water melds to Caribbean blue, then clear as cut glass at its edges. Day boats bob at their moorings and, in the distance, the cloud wreathed peak of Ben More, the highest in the Scottish isles, smoulders with deserved insouciance. In fact, I’m so preoccupied that I almost miss the hand-painted sign and have to brake suddenly before the world falls away again like a tailor’s tape unravelling. Rummaging in my panniers, I find some loose change and exchange it for a feathery half dozen eggs.

Vegetation thickens as I continue to descend. Grand trees droop, almost over the road in places, and lush fern blankets quiver in the languid breeze. The air here is much warmer. It envelops then washes past in balmy pockets, a feeling like swimming through sun dappled water.

Beside the grey harled box of Kilninian church I sit, gazing at Loch Tuath frothing at the hems of Gometra. Somewhere down there on the low threadbare outcrop, millionaire landowner and environmentalist Roc Sandford - named for Saint Roc, patron of mad dogs, sea storms and the falsely accused - is striving to save the world’s oceans, alone and unwashed, from the inside of a shed.

The road at Torloisk splits, heading in one direction towards Dervaig. Two cars’ standoff beside a smattering of stone cottages, a Land Rover with a dented stock trailer and a farmer straight from a porridge ad. He sits astride a sun-bleached quad, whistling up a squad of writhing collies. Some already cling to the back, in an old fish box, others sniff around my wheels until, at a word from the farmer, they swarm back to his side. He nods as I zoom off, amidst the sweet grassy perfume of petrol and lanolin and island industry.

Until now I have been profligate with my battery. Top speed is, of course, the most entertaining, but with the long climbs at Acharonich and the return leg still to come, I reluctantly drop a gear, (they’re quite unrideable with no juice). The greater effort warms my back, such that I stop and remove my windcheater at the Henhouse Cafe: clifftop purveyor of scones, sausage rolls and staggering scenery.

At Ballygown, a mile and a face-aching downhill section further, another sign draws me in. BREAD FOR SALE is picked out in painted letters on a hinged, hutch-like box. A fishing boat waits patiently on a trailer in the layby, rods sticking out of the sides like an insect’s legs, but I squeeze past it to discover a cache of sourdough still warm from the oven. Steam rises as I open the lid. My stomach growls.

A little further on, passing a mighty elm that’s probably watched over this road for two hundred years, I hear the thundering base note well before I come upon it. It carries like music above the hills, over the tinkling burble of peat-brown water on smooth rock and the chatter of birds and the hum of wasps and dragonflies. And soon the tumbling, seething long drop of Eas Fors waterfall lays its soporific white noise too, over the hiss of the camp stove and the crack and sizzle of fried bread and eggs in the pan.

Five men. Six oars. 3000 miles

It all begins with an idea.

The Scotsman, July 2021

It speaks volumes about the British obsession with a particular brand of humour that, despite the vast stretches of open sea, muscular thirty-foot Atlantic swells, sunburn, sores, sleep-deprivation, seasickness and suffering (lots and lots of suffering) that awaits the strapping lads showing us around their shiny new boat, what most people seem really, forensically interested in is not the buttock-clenchingly gruelling thought of propelling a fiberglass capsule no larger than a transit van one-and-a-half million oar strokes across an inhospitable ocean. It is the facilities. Or rather, the distinct lack thereof. So let’s get this out of the way early shall we.

It’s yellow and it’s plastic and it has, for my money, the easiest gig on the boat.

The Talisker Whisky Atlantic Challenge is billed as the world’s toughest row. In early December, crew members from around thirty global teams will cast off from San Sebastián de La Gomera on the coast of Spain’s Canary Islands, sculling for two hours then sleeping for two, on constant twenty-four-hour rotation, for between forty and one hundred days, until they reach Nelson’s Dockyard English Harbour in Antigua some three thousand miles West. Hopefully, in first place. They will carry (or desalinate) everything they need to sustain them on their journey, sleep and wait out bad weather folded into one of the boat’s two cramped cabins (cabins that, for buoyancy reasons, must be sealed shut whenever they are in use) and will, on occasion, be bobbing around atop a body of water that is over five miles deep. And I know that sounds like a lot of fun, but as I discovered when I visited the only Scottish crew in this year’s race (Five in a Row) at North Berwick harbour this bright morning, for them there is a deeper and far more personal reason behind this particularly flagellant pleasure cruise.

Rett Syndrome is a rare post-natal neurological disorder that affects brain development in children, resulting in severe and destructive mental and physical disabilities. Speaking, walking, eating, even breathing is impacted, whilst the parts of the brain that control consciousness and awareness remain largely undamaged, often locking young minds into young bodies they cannot control. In a particularly ugly twist, Rett is disproportionately fond of little girls. It is, and I choose this word carefully: heartbreaking. There is no known cure, at least not yet, but what can be managed is the health and wellbeing of the children and the families who suffer, as treatments, therapies, and hopefully a cure are developed. Ross McKinney, one of the five crew members putting the juniors of the North Berwick rowing club through their paces on the rowing machine, has a young daughter, Eliza, who suffers from Rett. Reverse Rett is the charity for whom the team are raising both money and awareness.

‘If it looks like a mid-life crisis and sounds like a mid-life crisis…’ Duncan Hughes is a head and shoulder taller than the rest of the crew; tanned, team-spirited, and terminally optimistic (and half a lifetime ago we went to school together). He doesn’t get a chance to finish his thought though, as one of his three young boys bounds up, tugging impatiently at his shorts. ‘We know you have money for ice cream!’

His ‘nope’ is accompanied by warm laughter and punctuated with a kick to the rear that sends the boy skittering and giggling away onto the beach. (They will try again three times in the next thirty minutes, using a variety of tactics, and eventually, sorry Hannah, they will wear him down.)

When the two of us were boys ourselves, some twenty-five years ago, Duncan was a vegetarian, as he still is today. This was a rare thing for a thirteen-year-old rugby player in East Lothian, and something he decided for himself was important — a fact I did not know until this moment.

‘Imagine a rugby club dinner where you are the only vegetarian. A lukewarm Linda McCartney lasagne being slow clapped in on a silver platter in front of the entire bar, and then a bill for forty quid!’ And yet it is a feature of the man that this, for him, is a fond and entertaining memory. I suspect this stands him, and his associates, in good stead for dealing philosophically with two months of his cacophonous dehydrated mung bean emissions. Which brings us smoothly to food. How, on earth, to feed five calorifically deficient rowers for ten ravenous weeks, with no fridge, cooker, sink, utensils, or support?

‘Freeze dried…it’s pretty good actually’ says Ian Baird, another of the crew, as he throws me a crinkled foil brick. A good thing too, as they’re going to have to eat a hell of a lot of it. Each man will need to consume approximately ten thousand calories, and around ten litres of water per day (which, if the solar powered desalinator fails, will need to be hand pumped; an agonising and laborious process). The hold will be packed — literally, to the gunwales — with vacuum sealed silver sachets of the stuff: protein, carbohydrate, sugar…and noisome arguments in waiting.

‘You eat the first thing you grab, and to begin with it’ll be jammed into the cabins too. We’ll have to squeeze in there with it until we’ve chomped our way through it!’ Adds Ian, gleefully.

The trip itself does not weigh anchor for some two hundred days, but already the crew are pushing themselves with punishing, and of course often socially distanced training, including brutal sets of two hours on - one hour off - two hours on (and if you’ve ever used a rowing machine I defy you not to wince at the very idea of that) as well as regular sponsorship rallying; glad-handing with everyone from sea scouts to venture capitalists. And no wonder, because it’s an expensive business. The boat itself costs in the mid five-figures, and that doesn’t begin to account for the entry fees, food, equipment, or the logistics of actually transporting crew and craft to the Canaries.

In an effort to broach the sensitive subject of finance, I ask Duncan how they found the boat. Surely, I thought, there must be no shortage of jaded, tattered-bottomed adventurers just desperate to get shot of the bloody things? But apparently not.

‘Hen’s teeth. We hunted and hunted, then one day I recognised three guys on the beach eating fish suppers. The Maclean brothers: Scottish ocean rowers, record-breakers. I ran over, got to talking with them and offered to buy their boat…they said yes, and we’ve had three offers for it already.’

So, the boat is expensive, and the accommodations cramped (and stifling, and windowless). The physical challenge is unrelentingly arduous, and the food is a little samey. You make the water yourself, puke yourself blind (did I mention that?) torture your bottom and relieve the monotony by jamming it into a bucket. Nonetheless, the lot of them look energised, elated, primed…near giddy with the thought of testing themselves, of doing something outside of the normal sphere of existence. But perhaps that is because there is more at stake here than just adventure, machismo, and a near palpable competitive spirit.

Perhaps that is because of Eliza.

Follow thier progress or support the team here: https://www.fiveinarow.co.uk/personal